- Home

- Bill Cunningham

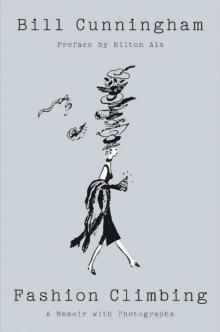

Fashion Climbing

Fashion Climbing Read online

PENGUIN PRESS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright © 2018 by The Bill Cunningham Foundation LLC

Preface copyright © 2018 by Hilton Als

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

All images, unless credited below, are by Bill Cunningham. Photographs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 by Anthony Mack. Used with permission.

Photographs and illustrations 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, and 17 appear courtesy of The Bill Cunningham Foundation LLC.

9780525558705 (hardcover)

9780525558712 (ebook)

Penguin is committed to publishing works of quality and integrity. In that spirit, we are proud to offer this book to our readers; however, the story, the experiences, and the words are the author’s alone.

Version_1

CONTENTS

TITLE PAGE

COPYRIGHT

PREFACE BY HILTON ALS

The Doors of Paradise

Becoming William J.

My First Shop

A Helmet Covered in Flowers

The Luxury of Freedom

Nona and Sophie

The Southampton Shop

Fashion Punch

The Top of the Ladder

On Society

On Taste

Laura Johnson’s Philosophy

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

PREFACE

by Hilton Als

I loved him without knowing how to love him. If you think of love as an activity—a purposeful, shared exchange—what could anyone who was lucky enough to be acquainted with Bill Cunningham, the late, legendary New York Times On the Street and Evening Hours style photographer, writer, former milliner, and all-around genial fashion genius, really offer him but one’s self? I don’t mean the self we reserve for our deepest intimacies, the body and soul that goes into life with another person. No, the Cunningham exchange was based on something else, was profound in a different way, and I think it had to do with what he inspired in you, what you wanted to give him the minute you saw him on the street, or in a gilded hall: a certain faith and pride in one’s public persona—“the face that I face the world with, baby” as the fugitive star, the princess Kosmonopolis, has it in Tennessee Williams’s Sweet Bird of Youth. Like the princess, Bill knew a great deal about surfaces; unlike the princess, though, he was never fatigued or undone by his search for that most elusive of sartorial qualities: style. You wanted to aid Bill in his quest for exceptional surfaces, to be beautifully dressed and interesting for him, because of the deep pleasure it gave him to notice something he had never seen before. Even if you were not the happy recipient of his interest—the subject of his camera’s click click click and Bill’s glorious toothy smile—there were very few things as pleasurable as watching his heart beat fast (you could see it behind his blue French worker’s jacket!) as he saw another fascinating woman approach, making his day. That’s just one of the things Bill Cunningham gave the world: his delight in the possibility of you. And you wanted to pull yourself together—to gather together the existential mess and bright spots called your “I”—the minute you saw Bill’s skinny frame bent low near Bergdorf’s on Fifth Avenue and Fifty-Seventh Street, his spot, capturing a heel, or chasing after a hemline, because here was your chance to show love to someone who lived to discover what you had made of yourself. His enthusiasm defined him from the first. It permeates this, his posthumous memoir, Fashion Climbing, which covers the years Bill worked in fashion before he picked up a camera. (He published only one book during his lifetime, 1978’s Facades, which starred his old friend, portraitist Editta Sherman, dressed in a number of period costumes Bill had collected over the years. He was not happy with the book but he was a perfectionist and anti-archival in his way of thinking, so how could a book satisfy his need to move forward, always? Fashion Climbing is, in many ways, his most unusual project. Of course at the end of his memoir he uses his story to help point the way toward fashion’s future.)

As a preternaturally cheerful person, Bill seemed not to ever feel alone—after all, he had himself. Born to a middle-class Irish Catholic family in Depression-era Massachusetts, Bill was raised just outside Boston; as a little boy he loved fashion more than he longed for anything as unimaginative as social acceptance. He begins Fashion Climbing this way:

My first remembrance of fashion was the day my mother caught me parading around our middle-class Catholic home. . . . There I was, four years old, decked out in my sister’s prettiest dress. Women’s clothes were always much more stimulating to my imagination. That summer day, in 1933, as my back was pinned to the dining room wall, my eyes spattering tears all over the pink organdy full-skirted dress, my mother beat the hell out of me, and threatened every bone in my uninhibited body if I wore girls’ clothes again.

A familiar queer story: being attacked for one’s interest in being one’s self. Still, there is no rancor when Bill says: “My dear parents gathered all their Bostonian reserve and decided the best cure was to hide me from any artistic or fashionable life.” But this was not possible. He would be himself, despite the pain. After he found work as a youth in a high-end department store in Boston, there was no stopping him, really, and no turning back. After Boston, the move to Manhattan where he lives for a time with more disappointed relatives, secures a job at Bonwit’s, and designs his first hats. The startling optimism of his outlook! In 1950, when he was twenty-one, he was inducted into the army. “At first I was heartbroken at the thought of giving up all the years of hard work,” he writes, “but I never had a mind that dwelled on the bad. I always believed that good came from every situation.” He would love despite the cruelty he had been given. It’s like watching a movie—Bill post-Bonwit’s, working as a janitor in a town house in exchange for a room to show his hats. The other residents are straight out of Truman Capote’s Breakfast at Tiffany’s and still, despite the mayhem—there’s even a flood—Bill presses on, and presses against our hearts because of his acceptance of others while maintaining very strict standards for himself. Living on a scoop or two of Ovaltine a day when things just weren’t happening financially, he fed on fashion and beauty; there was no shortage of it in all those glistening store windows advertising so much that’s been forgotten. I don’t think it’s too much to compare Bill to the Catholic art collectors John and Dominique de Menil, who regarded their commitment to beauty and supporting artists as a spiritual practice, a form of attention that was a kind of loving discipline: you could love God through his creators and their creations. There’s a nearly unbearable moment in the 2010 documentary Bill Cunningham New York when Bill is asked about his faith—his Catholicism. It’s the only time he turns away from the camera; his body folds in on itself. I turned away from the screen in that moment, just as, when Bill was the smiling recipient of the Council of Fashion Designers of America’s Media Award in Honor of Eugenia Sheppard in 1993—he collected the award on his bicycle perch, of course—I turned away, too: How could such goodness be possible? In the world of fashion? Such tenderness—it would kill you and Bill if he didn’t have an essential toughness, too, a way of looking at fashion’s transformative value, its ability to make and remake the spirit, without being sentimental about it, any of it.

Fashion Climbing more or less closes with his realiza

tion that hats are going out of style and the originality he ultimately achieved as a milliner is to no end because by 1964 who wears a hat? “Constant change is the breath of fashion.” Bill proves, in Fashion Climbing, that having a fashion personality is distinct from being a person who’s interested in style, and how style grows out of the kind of self that turns the glass of fashion to the wall. (As writer Kennedy Fraser observed, style is fashion’s “anarchic” cousin who refuses to play by the rules.) Toward the close of Fashion Climbing, Bill writes: “The wearing of clothes at the proper place and time is so important.” That’s because they tell a story—not only about the wearer, but also about her time. How dare one not pay attention to the world one lived in, a world filled with the gorgeous tragedy of what is happening now, never to be repeated. For the fashionable minded (Bill never liked ladies in “borrowed dresses,” he said) and other followers of the herd, Bill offers a kind of prayer:

Let’s hope the fashion world never stops creating for those few who stimulate the imaginations of creative designers, and on wearing their flights of fancy, bring fashion into a living art. There’s only one rule in fashion that you should remember, whether you’re a client or a designer: when you feel you know everything, and have captured the spirit of today’s fashion, that’s the very instant to stand everything you have learned upside down and discover new ways in using the old formulas for the spirit of today.

The light that lit Bill from within—his heart light—was that of a person who couldn’t believe his good fortune: he was alive. And I’m sure Bill knew that part of the privilege of life is our ability to have hope, that which is the backbone of all days.

The Doors of Paradise

My first remembrance of fashion was the day my mother caught me parading around our middle-class Catholic home in a lace-curtain Irish suburb of Boston. There I was, four years old, decked out in my sister’s prettiest dress. Women’s clothes were always much more stimulating to my imagination. That summer day, in 1933, as my back was pinned to the dining room wall, my eyes spattering tears all over the pink organdy full-skirted dress, my mother beat the hell out of me, and threatened every bone in my uninhibited body if I wore girls’ clothes again. My dear parents gathered all their Bostonian reserve and decided the best cure was to hide me from any artistic or fashionable life. This wasn’t hard in suburban Boston; a drab puritanical life prevailed, brightened only by Christmas, Easter, the Thanksgiving Day parade, Halloween, Valentine’s Day, and the maypole costume party in kindergarten. My life was lived for each of these special days when I could express all the fancy thoughts in my head. Of course, Christmas was the blowout of the year, and I started wrapping the packages months before anyone dreamed of another Christmas. The tree ornaments were packed away in the attic, where I usually dusted them off with a trial run in midsummer and prepared a plan of decoration for the coming season.

When Christmas came, I must have redecorated the tree a half dozen times in the short week it was left to stand, and when New Year’s Day arrived and the tree was to be thrown out on the street, a deep depression usually set upon me, as I tucked all the glamour, the shiny tinsel, away for another eternally long year, and only the thought of Valentine’s Day with its lace-trimmed displays of love made life bearable.

Easter Sunday was always a high point. I can remember every one of Mother’s hats, which were absolute knockouts to my eyes, but when I look back today, they were all very conservative. My two sisters and brother Jack (who was all sports-minded) and I were outfitted in new clothes for Easter Sunday. This was the dandy day of my life. I can’t remember a thing the priest said during Mass, but I sure as hell could describe every interesting fashion worn by the two hundred or so ladies, and for the following few Sundays I kept an accurate record of which ladies wore their Easter Sunday flower corsages longest, emerging from the refrigerators for the Sunday airing.

The next excitement I can remember was the maypole costume party where I managed, much to my conservative family’s embarrassment, to be a crepe paper pansy, violet, or daffodil. I always had a ball playing make-believe, and usually got hell when my mother got her hands on me, as I’d play with the girls, mainly because their costumes were the most beautiful roses. The boys were bees and caterpillars, which didn’t interest me a bit.

Summers were a fashion desert. Our small beach house on the south shore of Boston allowed nothing but bathing suits and T-shirts, and lots of horrible sunburn on the miles of salty beach. No one ever wore anything colorful or gay. Each Sunday’s church was the only adventure as my brother and sisters and I were wrapped in starched white clothes and chalk-white shoes. During the reading of the Gospel, I eyed every woman and decided who was the most elegant. It was a wonderful game, and by the end of each summer I would produce my list of the women at the beach whom I thought most exciting.

Going back to school was really the monster for me. I couldn’t have cared less about reading, writing, and arithmetic—and they cared much less for me! It was only through the grace of God and the teachers, who didn’t want to have me around another year, that I finished each school year. The only class I remember was a weekly one-hour art session where the most delightful, slightly eccentric teacher would read Winnie-the-Pooh and tell us about Mrs. Jack Gardner’s Venetian palace, set in Boston’s Back Bay. This was my hour of pure dream and fantasy. Of course, I immediately fell passionately in love with Mrs. Jack Gardner and her gilded palace, and to this very day she is my inspiration.

Life really began for me on my first visit to Mrs. Jack’s. That marvelous art teacher took the class to view what she called a “Renaissance splendor.” It was the opening of the doors of paradise for me, and there was no stopping my desire to create a world of exotic beauty. No matter how many times my mother caught me wearing my sister’s first long party dress, which was peach satin—and I know I wore it more than she did—I knew my destiny was to create beautiful women and place them in fantastic surroundings.

After school was the most fun, as I would hide in my room and build model airplanes and theatrical stage sets. Each month I would concoct a special display for the season, and I was forever talking the girls next door into putting on a dramatic play where I made all the crepe paper costumes and usually ended up wearing the highest crown or the longest train of purple, trimmed with my dad’s notepaper ermine tails.

Mother’s wedding gown, covered with embroidery and pearls and tiny satin roses, was the hidden treasure that I was constantly unpacking for another look. Actually, it was the only beautiful thing in the house.

Radio was a huge influence, to which I give credit for my strong imagination. Instead of doing school homework, I would be listening to Stella Dallas, Helen Trent, and my favorite, Helen Hayes, who led the glamorous New York life. In my imagination I dressed each of these soap opera ladies, designing for them all sorts of fancy clothes.

As kids we weren’t allowed to go to the movies except on Saturday afternoons, when some rough-and-tumble cowboy affair would scramble across the screen. I couldn’t have cared less; I was just itching to get back to the movies on a Saturday night instead and see Greta Garbo, Carole Lombard, and Gone with the Wind. Unfortunately, I never made it, and these movies remained totally unknown to me until the late 1950s, when I saw them in revival.

In later years, after-school jobs were part of my upbringing, which I enjoyed very much, as they paid me money that I promptly spent on something colorful and pretty at the local Woolworth’s five-and-dime. Shoveling long driveways of snow allowed me to indulge in elaborate gifts for my mother and sisters; I would shovel snow all day long just to get my frozen hands on some money to buy beautiful things. One time I bought the supplies to make a hat. It was a real dilly—a great big cabbage rose hung over the right eye, and all sorts of ribbons tied at the back of the neck. My mother nearly collapsed in shame when she saw it.

I was a newspaper delivery boy at twelve, and each morning got up at five thirty to pedal my bike around the nei

ghborhood and collect five bucks at the end of a week. After the first month, I saved my money, slipped in to the city of Boston on my first trip, and bought a dress, which I thought was the most chic thing in town. It was black crepe and bias cut, and had three red hearts on the right shoulder. As usual, Mother nearly had a fit. Now I was buying her clothes. Her reply was, “Think what the neighbors will say!” These were famous last words with my mother and dad.

My family had a whispering thought that I’d be a priest. And all this attraction to feminine fashion didn’t help their hope. But what Irish Catholic family didn’t dream of its eldest son being a priest? I always knew I wasn’t priesthood material as I was sewing away from some devilish fire, flaming inside the deepest corners of my soul.

The paper route made life worthwhile, giving me the loot to indulge in a little fashion fantasy, and as fast as I’d buy the newest styles, Mother would return them. I would counteract with another dress or fake diamond bracelet. My next job was delivering clothes for Mr. Kaplan, the local tailor. This was the beginning of my understanding what made beautiful clothes. Here I learned all about the construction of coats and suits, the fine technique of pressing and shaping. I also earned more money, and my two sisters soon fell under my assault of buying clothes, always making secret trips to the city and visiting the fashionable stores. My favorite was Jays on Temple Place. The facade of the terra-cotta-colored building was decorated with silhouetted ladies sitting on French chairs, admiring themselves in the style of 1910. Inside, the smell of perfume and champagne and wall-to-wall carpet made me want to buy everything in sight. They had the best-looking shopping bags in Boston, with a silhouetted lady and the name Jays giving the carrier great distinction. Of course, I was proud as a peacock, carrying the package home to my middle-class neighborhood. (I was the worst snob in town.)

Fashion Climbing

Fashion Climbing